Story by ALEXANDRA OGILVIE

Julius Ulugia is a Samoan American in his second year at the University of Utah School of Medicine. He helps to operate the University of Utah Pacific Islander Medical Student Association (PIMSA). According to their currently cached University of Utah club website, the mission is, “To provide students and mentors with a venue to network, increase awareness, promote and advocate, serve our Pacific Islander communities, and prepare for careers in medicine, healthcare, and administration. PIMSA provides peer mentors and role models for students seeking to enter academic and clinical healthcare fields.”

PIMSA was started in 2008 by Jake Fitisemanu Jr. and Kawehi Au. But, “it essentially became dormant when those who started either sought other careers or graduated and went off to residency,” Ulugia said. Currently, Ulugia is the only Pacific Islander in his medical school class of around 130, according to the school.

“Many people, Pacific Islanders and non-Pacific Islanders alike, see us as great athletes. That is literally what I got from my own family and non-Pacific Islanders. Many of us don’t see ourselves as intellectually equal to other people. This is magnified in health care, where we are unable to sufficiently care for our own,” Ulugia said in an email interview.

Fitisemanu wears many hats in the Utah Pacific Islander community. Among other things, he works at the Utah Health Department, he chairs the Utah Pacific Islander Health Coalition, and he is an elected representative for West Valley City. “PIMSA was a great opportunity for medical students to get involved in our own ethnic communities and expose other youth to possibilities in health science careers,” he said in an email interview.

“PIMSA has helped at least eight Pacific Islander pre-meds who have been accepted to med schools, and at least that many who have prepped for the MCAT and applied to medical school,” Fitisemanu said. Although it started off for MD students, it has branched to include other health sciences fields like nursing, physician assisting, dental, and pharmacy. Since there is only one Pacific Islander MD student in the state (Ulugia), the focus has shifted to undergrads rather than graduate students.”

Vainu’upo Jessop, a Samoan American anesthesiologist attendant, helped to found PIMSA when he was an undergraduate student at the University of Utah. He went on to complete medical school at the University of Utah. He was only one of four Pacific Islanders in his class and the first Samoan American to graduate.

PIMSA’s current focus is on Pacific Islander high school and undergraduate students. One way they excite high school students is to bring them to health conferences held at the University of Utah and Salt Lake Community College, to show them cow heart dissections and other exciting demonstrations. PIMSA also works on a one on one basis to help students navigate the college process.

“A lot of the [Pacific Islander] college students are first-generation students, and we would help them with the logistics of how to set up their schedule in order to optimize their chances for success at the undergraduate level. We would also get these people more involved in increasing awareness in the [Pacific Islander] community by having them run booths at health fairs, participating in after-school programs to promote healthy lifestyles, etc,” Jessop said in an email interview.

Jessop left town to do his residency at the University of Massachusetts in Worcester, Massachusetts, from 2012-2016 and completed a fellowship in critical care from 2016-2017. He returned home to Utah soon thereafter.

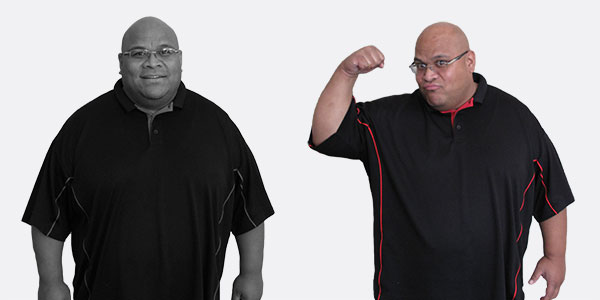

“Since I’ve moved back, I’ve had many [Pacific Islander] patients who are shocked to find out I’m a doctor. They ask me if I’m Polynesian, and when they find out I am, they usually say, ‘Wow! I didn’t know that there were any Polynesian doctors!’ I hope to be an example to other [Pacific Islanders] and show them, that we can make it,” he said.

Jessop believes that getting more Pacific Islanders into medical professions would increase the health of Pacific Islanders in the state. Currently, Pacific Islanders lead the state in incidents of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity, according to the Utah Department of Health.

“A lot of the older [Pacific Islanders] either don’t feel the need to see a medical provider, they don’t understand what a provider is telling them, or they flat out don’t trust people in the medical establishment. I think the more [Pacific Islander] providers there are in the community, the easier it will be to increase health awareness in the community,” he said.

Alyssa Lolofie, a Samoan American PIMSA member who is about to start medical school at Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic Medicine, agrees. “It’s important to get more [Pacific Islanders] interested in medicine (medical school, physician’s assistant programs, nursing, etc.) to increase representation and education on Western or mainland medicine for these [Pacific Islander] communities. Many patients with diverse backgrounds or from underserved communities are less likely to see a medical provider because of an assumed lack of understanding of the traditions and ways of life of these communities,” she said in an email interview.

Jessop added, “Overall, as more [Pacific Islanders] we can get into college and get professional degrees, there will be an overall increase in awareness in the community. I believe the benefits are twofold: the overall health of the [Pacific Islander] community will improve, and the younger PIs will see this and want to contribute.”

Two other organizations could potentially be helpful: the Asian Pacific American Medical Students Association and the Health Sciences Multicultural Student Association of Utah.

Filed under: Education, Medicine, Organizations, Pacific Islander | Leave a comment »