Story and photos by WOO SANG KIM

Statistics on domestic violence are appallingly high among Pacific Islanders. But a Utah nonprofit is offering seminars to educate men and women about domestic violence and provide information for disrupting the cycle.

According to a 2017 study, “Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault in the Pacific Islander Community,” “With regard to domestic violence and sexual assault, UN Women estimates that 60-80 percent of Pacific Islander women and girls experience physical or sexual violence by a partner or other in their lifetimes. The rate is higher than any other region in the world. Few countries in the Pacific Islands have laws against violence against women.”

What is the cause? Erin Thomas, a researcher at American University and author of the study, wrote, “The effects of climate change often emphasize gender disparities and result in greater violence against women. Additionally, political turmoil, violence, and poverty in many areas of the Pacific Islands increase the prevalence of gender-based violence.”

Oreta Tupola, community health specialist at the Utah Public Health Association, said, “The culture also prevents women from taking action.” Most Pacific Islander women take care of the household while the men earn income. She said women rely on men for financial support. Victims’ relatives do not meddle in the family business and let the family resolve the issue. The religious orthodoxy does not encourage people to challenge traditional family roles. In short, Tupola said women are left helpless and uneducated on how to stop the abuse.

- Tupola serves as an advocate assisting and advising women in danger to avert domestic violence.

Pacific Island Knowledge 2 Action Resources (PIK2AR), founded in 2015 by Susi Feltch-Malohifo’ou, Simi Poteki and Cencira Te’o, is a group of activists who speak up to inform the community about the domestic violence, cultural preservation, and economic impact. The mission of the organization is to provide resources, opportunities and services to Utah’s Pacific Islanders by bridging communities.

PIK2AR’s domestic violence program focuses on unique messages for men and women. The Pacific Island Women’s Empowerment (PIWE), seminar featuring workshops and group discussions created by PIK2AR for women, hosts two weekly sessions for both Pacific Islanders and non-Pacific Islanders at the Sorenson Unity Center at 1383 S. 900 West in Salt Lake City. The seminar lasts about 90 minutes and has about 17 participants.

Feltch-Malohifo’ou, PIK2AR’s executive director, said, “We teach how to pay the bill, raise the credit score, and what domestic violence is by definition, which starts way before the first punch.”

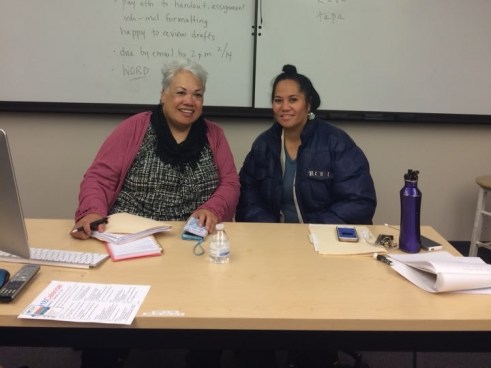

- Feltch-Malohifo’ou (left) is executive director of PIK2AR, which provides safe passageways for women who are victims of domestic violence to liberate from their husbands.

Tupola said the PIWE offers a curriculum that gives therapy, group sessions on empowerment and strength, how to remove children safely, where to find shelter, how to have a safety plan, how to detach emotionally from a spouse, and how to prepare for separation. The PIWE also rotates speakers specialized in social work and behavioral psychology weekly, too. Every seminar, the speaker prepares different topics as requested by the guests and answers questions that are taboo in the Pacific Islander culture. Tupola said such are sex, drugs, and personal lifestyle.

Women at the varying stages of victimization are aided. “They don’t just come because they are just trying to run away. They have not decided if they want to leave but come in for therapies and advices,” said Matapuna Levenson, lead guide at the Salt Lake Area Family Justice Center. “We have a wide range of stages. They generally come to get a civil protective order. The protective order forbids abusers from contacting victims. Upon contact, police arrests them (abusers). Victims are surprised by the vast resources and helps out there,” Levenson said.

- Matapna Levenson provides resources, connections and advice for women who seek aid.

Although the door is always open for all victims, the aim of the PIWE is to teach women to be independent. “We don’t want people keep coming back to us for help,” Feltch-Malohifo’ou said. “We want to empower and teach so that they can help themselves.”

Levenson said, “Those able to sustain themselves and prevent themselves from abuse become advocates in issuing protective order, supporting other victims in healing, and speaking in domestic violence conferences.”

The PIWE shapes women to liberate and take actions from their husbands, Tupola said.

PIK2AR also offers a seminar, Kommitment Against Violence Altogether (KAVA) Talks, for men. The monthly seminar is held at the Oish Barber Shop in 4330 3500 South in West Valley City. It also lasts for 90 minutes and has about 13 participants.

Tupola said men are taught that “everyone has a right to be free of harm, domestic violence is against the law, respecting personal boundary is crucial, and that violence is not a discipline.”

She also said men were often unaware of this country’s culture and laws, and that their actions could result in deportation. Many have family history of domestic violence and have accepted it as a norm.

“This upbringing combined with stressors of living in a new environment, not finding a job, comparing their wife to other wives, and not having enough money prompts men to perpetuate the crime,” Tupola said. “The Western influence of spanking to discipline also reshaped men, too.”

What can we do? “Appealing to priests, bishops, and governors, becoming allies, and maximizing faith and family relationships is key to connecting the Pacific Islander community. Violence has nothing to do with culture and race. It crosses socioeconomic groups,” Levenson said.

Filed under: Health & Fitness, Legal Aid, Nonprofits, Organizations, Profiles | Tagged: PIK2AR, victim assistance | Leave a comment »