Story and photos by HANNAH CHRISTENSEN

Pacific Islanders who leave their homes and villages in search of a better life in Utah often experience culture shock and feel “stuck,” with no idea of what to do next.

Martha and Mike Meredith at their home in Millcreek, Utah.

Mike and Martha Meredith are Pacific Islanders who have overcome many social barriers in order to be living comfortably in Millcreek, Utah. Martha vividly remembers her father cutting down and cracking coconuts in Tonga and then watching her mother clean them out. Martha was 10 when her family left Tonga and moved to New Zealand.

That’s where she met Mike. Mike was born in American Samoa but grew up in European Samoa until his family moved to New Zealand when he was 13. Martha recalled, “My family went through several migrations, first among the islands, then in New Zealand, and finally to America. My sister came first, then my parents. Mike and I were married and we had two little children and a third on the way when we came. We had no idea what on earth we were getting into.”

These migrations seemed so natural for their families, Martha explained, but when they got to America and it was so vastly different, they felt isolated and trapped. They weren’t sure how to assimilate while remaining true to their cultural practices.

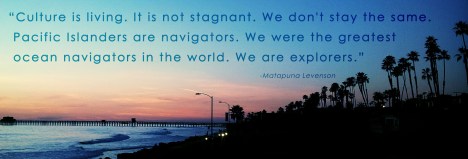

Matapuna Levenson, a lead advocate at the Salt Lake Area Family Justice Center, said, “Culture is living. It is not stagnant. We don’t stay the same. Pacific Islanders are navigators. We were the greatest ocean navigators in the world. We are explorers. So the idea of just staying the same, staying in one place, staying in one mindset, is so contradictory to the values that our culture is perpetuating and encouraging, what our ancestors were hoping for us.”

And now that these navigators are here, pursuing the American dream, what can they do? Where can they turn for help?

Jake Fitisemanu Jr., a clinical manager with Health Clinics of Utah, Utah Department of Health, said it is difficult for Pacific Islanders to navigate a social system that has completely different values because they aren’t sure how to do their part. In a village, everyone has their role and every role contributes to the overall wellness of the village.

According to the Utah Department of Health, “the overall proportion of NHPIs (Native Hawaiian Pacific Islanders) in Salt Lake City is greater than [in] any other city in the continental U.S.” One would assume that having a larger population would mean people have a community, a place to go, individuals who want to help. But what happens when those who came before you still feel adrift and disillusioned?

Fitisemanu wants to empower people who feel misplaced or lost. “I’m interested in mobilizing communities for political power, because this is the United States, that’s how it works here.” Fitisemanu sees the bigger picture after working for the government in the health department and as a city councilman for West Valley City. If the goal is getting Pacific Islanders to feel comfortable utilizing resources, then including them in the governing structure is one good way to do that.

Mike Meredith is another advocate for Pacific Islanders. He served on an advisory board for the Pacific Island community in Utah that focused on ways to improve education and resources for their communities. Because of his service on the board, Mike knows the issues that make it difficult for Pacific Islanders to start looking for resources, even if they are available.

“Especially in Utah, there’s a vast window that is open for them,” Mike said. “But one of the fears is picking up the phone, calling and setting up an appointment or approaching where there is help and seeking that. But it’s not really fear, it’s just something that’s in them, because they’ve lived in villages. You can go from home to the beach and throw in a fishing rod. Where here it’s wide open. They don’t know where to go or who to talk to.”

While it is true that the Pacific Islander population creates a place for tribal identification and emotional resources, Mike said there is confusion about how the American educational system applies. “The old tradition comes into this country and it’s difficult. Folks come in and think ‘you should have your kids finish school and then send them to work.’ That’s what we did back home. But that’s not the case that’s required here. To grow and progress you need education.”

Mike added that Pacific Islander parents lack the understanding of the benefits of graduating from college and entering the professional workforce. The family culture creates alternatives to college graduation and training required for high-level jobs, resulting in economic instability. The impact on families without sufficient financial stability affects all aspects of life — housing, medical care, food security — not to mention future school and work opportunities.

The Merediths are an exception because Mike was able to graduate with a degree in engineering and have a prosperous career. But he says this ethos was not easy to pass along even to his own children. And it is much more difficult for parents who feel at sea here in the high desert of Utah. Yet he still believes that Pacific Islanders can have it both ways — in his case American prosperity, along with a strong commitment to the values, mythologies, rituals and symbols at the heart of his Samoan-Maori culture and Martha’s Tongan culture.

Activists like the Merediths, Levenson, and Fitisemanu lead the way by empowering and educating Pacific Islanders. Fitisemanu said it is important to continue tradition while also moving forward. “We’re walking into the future backwards,” he said. “That’s how Polynesians see time. This is how we stay connected. Even though we’re moving in distance and in time into the future, we’re always facing the past.” Maintaining this connectedness while moving forward propels Pacific Islanders toward their dreams.

A quote from Matapuna Levenson, lead advocate at the Salt Lake Area Family & Justice Center.

Filed under: Immigrants & Refugees, Pacific Islander, Profiles | Tagged: assimilation, community, culture, mobilization | Leave a comment »