Story and photo by MCKENZIE YCMAT

We all have a story to tell, all we need is a platform to share it. Two women, Noelle Reeve and Hailee Henson, are both members of the Pacific Islander community and have stories that they believe will inspire people not just within their community, but all women in general.

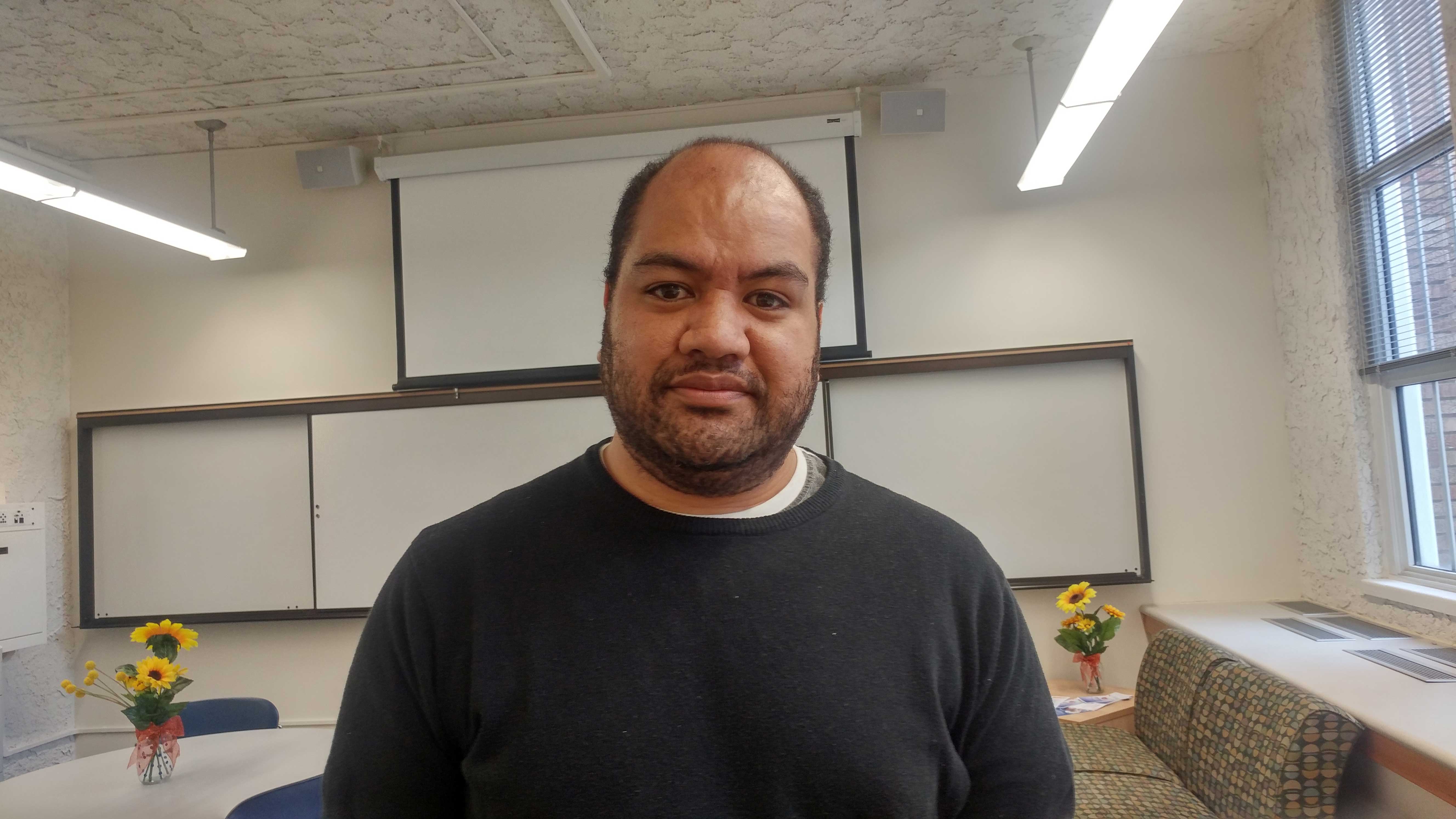

“I just want to be remembered,” said Reeve, a 23-year-old half Hawaiian woman from Sandy who was recently diagnosed with lupus. “I just want to tell my story like everyone else.”

Lupus is a common disease that causes the immune system to have a hard time telling the difference between good and bad substances going through your body. This forces the body to create an army of antibodies that attack good tissues, which can lead to mild and sometimes life-threatening problems.

Reeve started showing signs of lupus early in her teenage years and decided to visit her doctor after noticing she had become sensitive to light, struggled with fatigue throughout the day and experienced muscle soreness.

Noelle Reeve was diagnosed with lupus at age 20 and now tries to share her story.

“My first appointment was with a rheumatologist I found through Google,” Reeve said. “He looked me up and down and only asked short questions. Every time I would answer he would talk over me. I had hoped I would go in and spend at least an hour doing tests and figuring things out, but I was only with him for 10 minutes.”

After countless appointments with numerous doctors, Reeve felt like she was at a loss and needed to find another route to find the answers she was looking for.

“I realized I wasn’t being taken seriously because of my age, my gender, and possibly even my ethnicity,” Reeve said.

Researchers have found that 50 percent of non-white patients have lupus, compared with 25 percent of whites. Reeve finally discovered a small group of doctors who are aware of these facts and also are members of the Pacific Islander community.

“I felt like I finally found a place where people understood my disease and they also understood my heritage,” Reeve said.

The new group of doctors diagnosed Reeve with lupus and helped her find a treatment that fit her needs. She said she feels like she is managing her disease and living a healthy future.

“I finally feel like I have control of my life and I found it through my own community and my family,” Reeve said. “I hope one day I can help someone else as they have helped me.”

Reeve is trying to get more involved with her community and wants to help others find answers to their health questions by sharing her story with friends and family who struggle with the same things.

“It’s all about family in the Pacific Islander community and that’s the one thing I hope people take away from hearing my story,” Reeve said.

Susi Feltch-Malohifo’ou is the executive director of Pacific Island Knowledge 2 Action Resources, an organization that focuses on violence prevention, economic impact and education within the Pacific Islander community. ““Everything is for the family. That’s why we’re so good at sports, besides our build. It functions the same way as a family. All for one, all for one family,” she said.

Hailee Henson, a 25-year-old from North Salt Lake, grew up in a strong Mormon family but never knew her family heritage. Henson’s mother was born and raised in a white family, but her father was adopted as a child and never knew his ethnic origins.

“I served an LDS mission and spent 18 months with companions who were islanders from Tahiti,” Henson said in an email interview. “I always felt some sort of draw to them and special bond with them, but never knew why. They always joked that I was an honorary Tahitian.”

It wasn’t until early 2018 that her family decided to visit the Polynesian Cultural Center in Hawaii — a trip that pushed her father to get an official DNA test to find out which community he belongs to.

The day after returning home from their Hawaiian trip, the DNA test results had arrived. His father and mother were both Polynesian, making Henson a part of the 56 percent of the Native Hawaiian population to be considered as Polynesian mixed with another race.

“It felt amazing. It felt so right. Honestly, my family was so excited,” Henson said. “But like I said before, I’ve always felt so drawn to the Polynesian culture and this helped that tie make so much sense.”

Henson is currently studying to be a chef at the Culinary Arts Institute in Orem, Utah, and feels like her newfound identity has opened her eyes to a whole new menu.

After learning about her family heritage, Henson wants to understand more about Polynesian cuisine and share her findings with her family.

“I’m obsessed with Island cuisine. It’s such a simple way of life — eating off of the land and appreciating all that you’ve been blessed with,” Henson said. “The islands contain some of the best, fresh produce. They’re so blessed! I’d love to delve further into working with island cuisine and tropical fruits and fresh fish and all the good stuff.”

Reeve and Henson hope to make a change within the Pacific Islander community to show that women have a passion and a story to share that can change many — specifically those in their close communities — for the better.

Filed under: Food & Restaurants, Health & Fitness, Pacific Islander | Leave a comment »